Fixing the Throwaway Society

A new breed of makers – the fixers, is subverting the status quo by doing something that not so long ago was so commonplace, it was considered mundane: they’re mending their own stuff.

My son recently came home from cycling with rip in the elbow of his sweater. He had had a mishap with a wet patch of grit on the side of the road and had fallen of his bike. Fortunately, apart from some bruises and scrapes, he was okay.

The same could not be said of his phone. As with many teenagers, his smartphone is more an extension of his body than a separate entity. He uses it for playing, surfing the Internet and, of course, texting. It was precisely trying to text minutes after arriving home, when he noticed his mobile was refusing to connect to the network.

The only visible damage to the phone was a very minor dent in the case. Everything else worked fine: WiFi, camera, touchscreen, but no mobile network. The phone was an HTC One M8, and is irreparable in the sense that, by design, it is all but impossible to mend. There are no visible screws that allow you to open it. This, nowadays, is seen as normal, but it gets worse. The back of the phone is very strongly glued to the body, and even if you can get that off with special tools and a heat gun, more bits and pieces, including the motherboard and the screen, are glued together to ensure that, if you even did try to disassemble them, the whole thing would disintegrate in your hands.

A device that cannot make or receive calls or send texts without WiFi coverage, despite everything else working correctly, was no good to our son. And it was no good to us, my wife and I: as the helicopter parents we are, we could not ring our child to check up on him when he is out with his friends. So a shiny, unbelievably sophisticated 500€ device, the apex of modern digital communication technology, in nearly mint condition save for a small dent on the back, now lies dead to the world, in the dark recesses of the back of drawer in its coffin-box.

Systematic and Deliberate Disempowerment

There has been a systematic, deliberate and very successful movement to disempower consumers of electronics over the years. With the excuse of making devices sleeker, manufacturers have removed all visible point of entry to their devices; gradually eliminated replaceable parts, such as batteries and docks for external storage; and started using glue on everything.

Warranty conditions have become stricter to legally discourage users from tinkering with their machines and make it more difficult for users to demand refunds or replacements. This is often done in cohorts with shops who blatantly lie to consumers about their rights. Apple and HP, for example, claim that you are only entitled to a 1-year warranty, and shops will try to make you believe this is so (while at the same time trying to sell you an “extended warranty”). But, at least in the EU, there is a legal minimum of 2-year warranty period on all electronic products.

Warranty conditions have become stricter to legally discourage users from tinkering with their machines and make it more difficult for users to demand refunds or replacements. This is often done in cohorts with shops who blatantly lie to consumers about their rights. Apple and HP, for example, claim that you are only entitled to a 1-year warranty, and shops will try to make you believe this is so (while at the same time trying to sell you an “extended warranty”). But, at least in the EU, there is a legal minimum of 2-year warranty period on all electronic products.

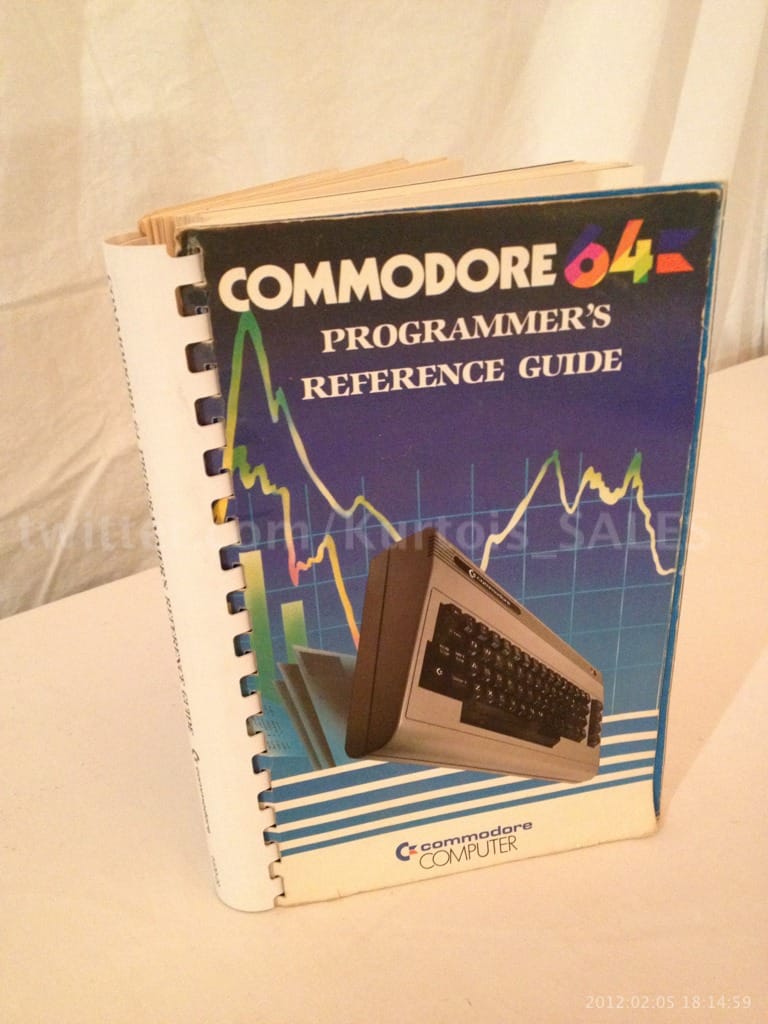

And what happened to manuals? They have become thinner and thinner over the years, until they have practically disappeared. This is has its up side: it saves on paper and, hence, protects the environment. But you, as a consumer, are missing out. Take, for example, my Commodore 64 manual from the mid-eighties, all 420 pages of it. Check out the last pages. Printing the schematics in the back of a manual was a common practice until, oh, 30 years ago? It seemed normal for manufacturers to give out the information you needed to maintain your own stuff. Getting this sort of information in a modern smartphone manual is unthinkable.

And then there’s the small matter of programmed obsolescence. Even if you take the most generous definition of the term, not the one that states that vital parts are designed to fail after a certain time (the duration of the warranty + 1 day), but instead that the durability of the materials can only be guaranteed for a certain lifespan, the fact still remains that our expensive devices, devices that pollute when they are built and pollute when the are discarded, are not made to last.

The Toll

And this is is probably the most grievous effect of throwaway electronics. After all, you can choose to have smartphone, you can chose whether to renew it after two years, or, you know, you can chose not to. What you can’t chose is the massive damage the consumer electronic industry and market forces are inflicting on your environment. The United States alone generates over 3 million tons of electronic waste a year. Landfills are clotted with non-biodegradable materials, and heavy metals from batteries and electronic components seep into rivers, lakes, and seas. Pollution is also generated when manufacturing new devices. That impacts our air, land and water too.

And if that were not bad enough, don’t forget the suffering the industry causes to workers worldwide. We have all heard and read about the inhumane conditions of workers in companies such as Foxconn, but the part of the industry concerned with the extraction of prime materials used in our gadgets is even shadier. So-called rare earths, used in many modern electronic components, have the adjective “rare” attached for a reason. Tantalum, an essential ingredient of the capacitors in your phone, fuels conflicts in central Africa that displaces, harms and kills thousands of people a year.

Manufacturers have been complicit with these conflicts, to such an extent that even the US Congress, always reluctant to interfere with the doings of American multinational companies, was forced to enact laws and intervene.

Finally, there is also the small matter of how much throwing away a device every time it breaks costs the buyers. But I am sure I don’t have to elaborate on that to make my point.

Fixing the World’s Gadgets

“It’s the worst feeling in the world!” exclaims BBC reporter LJ Rich at the beginning of a segment on the Fixer community. I wouldn’t go as far as that. After all, she had only broken the screen of her old iPad. But still, you’ve probably felt the same: you have this expensive piece of kit you rely on and, in split second of carelessness, it is headed for the rubbish bin and you are facing having to fork out 500 euros you hadn’t planned on spending.

As Rich soon discovered, feeling bad wouldn’t last long. She joined up with the Restart Project, a group of consumers who have taken the fate of their electronic devices in their own hands. The group supports with advice, workshops, meet-ups, and tools anybody who has decided to repair their own gadgets.

The organization has groups all over the world, although mainly in Europe and the US and organizes “Restart Parties”, one of which Rich attended to see if she could repair her iPad. As it turns out, getting her screen mended was more complex than she first thought, but she succeeded on her second try. The excitement she demonstrates at the end of the video, when her device works, is probably much more of a rush than going out and simply buying a new one.

And here’s the thing: Fixing may save the planet and save you money, but it is also fun. Crazy fun. Taking things apart has a universal appeal, and if your gadget is broken and not under warranty anymore, what do you have to lose? Plus there is the added thrill of, with the proper guidance, putting it back together and maybe even having it work again.

Where to get started

iFixit is probably a good place to start. The web contains detailed tutorials that explain how to take apart and repair many devices and is neatly divided in categories, including Mac Repair, Game Console Repair, and Phone repair. Drill down through any of the top categories until you find the exact make and model of the device you want to mend. All tutorials are carefully explained and illustrated all the way and include a description of the tools and techniques you need.

And if you haven’t got the tools, iFixit can help you there too. At the top of each tutorial is a list of the things you’ll need to successfully complete the task. Click _Buy these tools_ and you’ll access the store and you can have the implements and the parts used in the tutorial shipped to your home for a reasonable price.

iFixit.com’s sister site, iFixit.org, is home to the groups blog. In it you can read user stories, news, opinion pieces, about events and so on. You can read about Jessa Jones-Burdett, who, commited to repairing an iPhone her children had flushed down the toilet, taught herself microsoldering and now runs iPadRehab, a home business that fixes other peoples iGadgets; or how manufacturers, in the accelerating arms race to stiff consumers, have included DRM into everything, from coffee machines to kitty litter boxes.

The Explore menu leads you to links to other like-minded organizations’ websites, such as Repair Café, a network of European groups that help people repair their own stuff, from moth-eaten jumpers to electronics; or the Fixit Clinic, a Bay Area group that opens your broken appliances and teaches you how to mend them.

Fix it Now

Fixing is exciting, rewarding, and can also help save the planet without forcing you to give up your electronic toys. What’s not to like? If you’ve been bitten by the maker bug, check out you local fixer group (or, if there is none, start your own) and put your skills to work on a very worthy cause.

Do you belong to a fixer collective? Join Pling and tell us about your group and your activities. We’ll help you fund events and tools, and give you coverage to attract users to your events.